Tool Banditry and also a Modest Defense of Echo Chambers

If you get into the habit of reading blogs—as I so foolishly have—you’re going to be bombarded with a lot of well-reasoned and highly articulate worldviews that are fundamentally incompatible. The first mistake any novice ideologue makes is denying that their intellectual opponents have any point whatsoever. Trapped in the arguments as soldiers mindset, we cannot display weakness by ever yielding a point to our opponent. I hope it’s obvious why this is a bad technique for learning and communicating authentically.

You can easily find advice along the lines of “take people who disagree with you seriously” from many sources, but I feel that even the proponents of this idea are uncomfortable with its implications. To take it to the extreme: did the Nazis ever have a point, or are they a perfectly convenient example of an ideology that was somehow wrong about everything ever? If we yield that they ever had a point about anything even completely unrelated to the genocide parts, does that imply there’s some soundness to their worldview?

Here’s a secret nobody will tell you: when you are learning about new frameworks, you can just rip out the parts that ring true. In fact you can just rip out the parts you like, inasmuch as they are tools rather than claims. Academics in the humanities who have to write really long papers about every possible topic to justify their salary figured this out a long time ago. They will deploy a materialist | feminist | postcolonial | static | moral anti-realist analysis to any old subject and squeeze out 10k words of jargon and collect their paycheck, unbothered whether what they’re saying is authoritative or more correct or any other terminal goal you would have in a hard science.

Human experience is like a prism. Much can be gained by rotating it to a new point of view and studying that facet’s novel set of distortions. So while no one longwinded paper about imperialism in your favorite video game will be the last word, in aggregate the discussion will flesh out and enrich the topic.

Godwin’s Law

So am I saying there are facets to Naziism that warrant closer examination? I think it’s pretty clear that their ideology is just about the worst one out there and there’s a reason that it died such a quick and violent death and now we’re trying to do some form of damnatio memoriae to it. They also straightforwardly failed at their stated goals: their territorial gains were all erased within a few years, their racial enemies kept on existing despite their efforts to the contrary, and everyone in charge ended up dead or in prison. Fascism, failing to live up to its aesthetic promises, has an almost unbroken losing streak in wars of conquest. Naziism went away because it lost a Darwinian struggle against liberal democracy. It’s not just morally reprehensible, it’s wimpy and effete and was ground into the dirt by the boots of their supposedly weak enemies.

Even so, the pragmatic American military leadership understood the utility of tool banditry. At the close of the war, they discovered a wealth of human talent laboring to serve the party’s infinite appetite for killing machines. Naziism was bad at human welfare and winning wars, but it had created some truly impressive technology. So began Operation Paperclip, the smuggling of hundreds of German scientists and engineers into America. I do not bring this up to condone the operation—it seems a little morally dubious that you can escape the consequences of facilitating a war that destroyed so many lives just because of your scientific talents. But it is illustrative that even the most evil and destructive system the world has seen had created some functioning scientific apparatus buried under its layers of incompetence that could be extracted and put to better use. The Nazi innovations in rocketry and the subsequent large scale kidnapping of their top talent directly led to the success of the American space program.

The failure mode I am warning you off of with this extreme example is mistaking stealing a tool with an endorsement of the whole. America did not pilfer the German rocketeers because they secretly loved Naziism. Rather they secretly loved rocketry, and wanted to assemble the best set of tools at their disposal.

ad rem

At this point in my life I find that my beliefs about most topics are so impossible to capture as an ideology that there are very few individuals I can actually endorse to the hilt (Jesus Christ comes to mind). I consume a lot of writing that I almost entirely disagree with. I think that has helped moderate my approach to thorny problems and given me a unique mixture of opinions that defies easy categorization in whatever culture war framework you want to shove me into. It has also made me less hasty to go and shove other people’s ideas into categories, and less surprised when they embrace heterodox or even seemingly contradictory viewpoints.

Nevertheless, because I have witnessed a pattern of audiences treating a reference as an endorsement, it makes me reluctant to cite my sources. It’s very difficult to communicate the concept of: “you should check out what this guy has to say but only the good parts and yes I solemnly disavow these other parts” without losing track of the point you’re making.

I think a perfect example of this is the so called “manosphere”. In general they seem to possess toxic personalities and espouse this weird hypermasculinity that will make you immensely unpleasant to be around. They teach young men to be resentful and callous. But there are some deep truths at the core of their message that make it understandable why this bizarre influencer subculture lives on. Stuff like: man up, take responsibility, work on yourself, act on the world instead of only being acted upon, study the historical pedigree of western culture and understand how to cultivate the values that we claim to hold dear. Then they bend and twist it to appeal to the dark side of humans and maximize their algorithmic potency. It has become hard to find honest people forcefully advocating for these core values outside of the broader redpill movement due to the whole guilt-by-association procedure we do.

Sometimes I find myself drawn to dive into an ideological miasma and search for the flecks of gold in the mud slurry. I steal those, discard the rest, and then keep quiet about their provenance lest I am called cringe. It is poor form to criticize ideas because of who said them and in what context. That’s the ad hominem fallacy and genetic fallacy. Just let me steal ideas and cobble together my own worldview in peace. And hey, why not try it yourself? You may find that people you generally don’t agree with actually have a point sometimes. It’s fun to catch them off guard by embracing it and making it your own. You’ll also generally live a richer intellectual life by smashing all of the analytical frameworks together in random combinations to cook up novel ideas.

The strongest counterargument to Tool Banditry I can imagine goes something along the lines of: “You do not want to yield space for a problematic worldview to lay down a foundation. These are ideas in service of bad conclusions and you are allowing yourself to be led by the nose to them.” I think this feeling emerges from a certain lack of confidence in the rigor and defensibility of your own foundations. A lot of people are very outcome-focused when it comes to what they choose to believe, so they never take the time to derive those beliefs from basic principles and dive into the philosophical tradition surrounding them. I think that’s fine. Not everyone needs to be a debate bro. But it is something you would probably want to have in your toolbelt if you start coming after somebody else’s beliefs. The other place I think this counterargument comes from is a paternalistic concern for the credulity of the midwit public. And you know what, fair enough. I would not like to see somebody I love sent down a rabbit hole by a parade of “common sense” statements. But you, dear reader, are clearly an elite in this regard so we needn’t worry about you getting deceived by the tricksy thinkers.

EDIT: Two days after I published this, Brett Devereaux published a short critique of realist foreign policy. He included a throwaway paragraph that lines up exactly with what I’m trying to get at:

A case study: personality tests

Not all thinking tools are created equal. Some are more attractive because they play off of our cognitive biases and pattern-seeking proclivities, staying vague enough to never give away the game. Astrology is a great example of this. It is intellectual putty so malleable it can be crammed into any observation-shaped hole and purport to explain it after the fact, but will never prove itself to have any actual predictive power.

As for the more “scientific” measures of personality, their predictive power is also questionable. The entire field studying the science of personality has struggled to replicate consistently and across cultures, suggesting that they are failing to measure any innate characteristics at all. Nevertheless, I would rank something like The Big 5 as far more useful than Myers-Briggs (MBTI). Why? There is some level of predictive power to Big 5, however flawed and biased, that has withstood scientific scrutiny over several decades. Myers-Briggs on the other hand is a hiss and a byword amongst basically all serious professionals. But accuracy is only a weak reason to prefer it. The stronger reason, in my opinion, is that Big 5 is a far more useful framework.

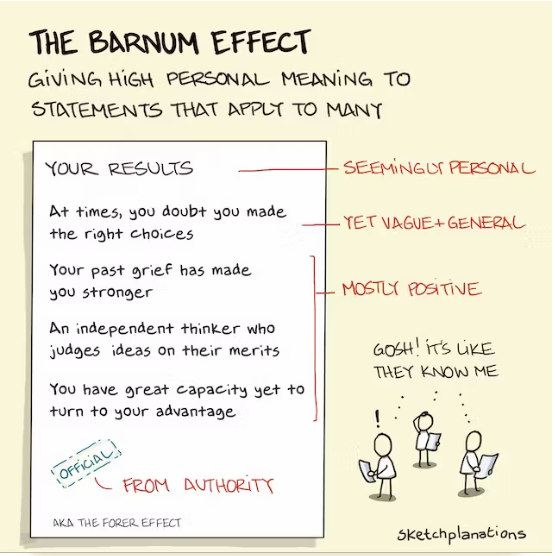

Think about it. It seems like Myers-Briggs appeals to the same people that astrology does. It has a similar number of categories that people are grouped into, with descriptions that leverage the Barnum Effect with vague flatteries.

My psychic senses are telling me that you are somebody who likes to read a blog of a handsome man

Like the esoteric mysteries of astrology, I get the sense that most of MBTI’s fans don’t even understand the specific claims it is making, just fixing their focus on the cute plain English explanations you get about your archetype. But above all there is one most fatal flaw for its utility as a discussion tool: it’s just a 4 bit integer. You are given a 4 letter acronym and each letter communicates a single bit of information. You present yourself as either “thinking” or “feeling”, not encouraged to center discussion around a score on a spectrum, even if the tests give you that bonus data sometimes. Most people never even glance at the other 15 archetypes, and if they did they would realize that some of them might actually fit them better than the one they’re assigned. And nobody but the most dieheard fans has the slightest idea what the difference between “Intuiting” and “Sensing” is, or “Perceiving” vs “Judging”.

Contrast this to Big 5: It’s just 5 scores. There’s no narrativizing about your special combination of scores sucking up all the oxygen. Each score independently has its implications, sometimes in combinations with others: high conscientiousness and low agreeableness are common in highly successful entrepreneurs. High openness and low neuroticism are traits of successful marriages. But accepting these conclusions isn’t necessary for it to be fun and thought-provoking to consider how differences in people might manifest, and Big 5 provides you the words to get the conversation going. This is the throughline with all the tools I like to steal: vocabulary to guide your thoughts and give voice to your intuitions. You obviously can’t accept the smuggled conclusions of the terminology prima facie, but even as a punching bag it’s still a useful intellectual gadget to adopt. So go out and steal some tools.

Wait, but then nobody is gonna understand you when you debut all the new jargon you just learned!

Echo echo echo echo

In computer science you can write some useful 20-line procedure and then reference it with a function, which can be thought of as shorthand for “insert these 20 lines here and give me back the output”. A world without functions would be a cruel world indeed, forcing us to copy and paste our 20-line procedure wherever we’d like to use it, restating the same calculations to give the same outputs for the same inputs. And if one of these procedures was altered to make it more correct or powerful, the others would still be in their old form! One of the thousand acronyms you learn in your CS undergrad is DRY: Don’t Repeat Yourself. Repeating yourself is how you let bugs and inconsistencies slip in.

An analogue to functions also exists in human language. We can access shared pieces of context through Coupling, given we feel confident that the same context will be available to both interlocutors. This can take the form of pop culture references, proverbs, historical references, idioms, truncated quotes. But the more you learn and the more tools you pilfer, the more you will find talking to people who do not share your context to be frustratingly time-consuming as you spend more time explaining other people’s words and ideas (in lower fidelity) than you do expressing your own unique syntheses. You’ll also have to relitigate a lot of issues that felt put to bed. Imagine a Christian trying to discuss theophany with an Atheist. They are going to be coming into the conversation with completely different starting points, aiming toward completely different ending points, and are probably going to end up discussing some rather more basic theology than what the Christian had in mind.

It’s not a bad thing to revisit your foundational assumptions to see if they’re solid. But if that’s all you’re doing, you don’t get much time for the dynamic and fun parts of thinking. So when you’re around people who share a similar context to you, be that an overlapping taste in media, a widely accepted cultural canon, or even a shared faith, you are immediately positioned more advantageously to cooperatively explore the things you agree on with a level of nuance and candor that outsiders simply couldn’t accomplish. You can access cached conclusions through short keyphrases and immediately launch into new territory. This is my favorite thing about the rationalists: love them or hate them, you can’t deny they do be reading a lot of the same blogs and can trim hourlong tangents from complex conversations by simply citing the title of some Yudkowsky article that everyone has read like one might cite a famous Bible verse at church. Conversation just glides when you’re on the same page for longer and can both venture out to the scary frontiers where your convictions break down.

What I’m rhapsodizing about is basically an echo chamber, right? There are also very interesting and edifying conversations to be had with people who share very little context with you and can thus impart alien perspectives and challenge prejudices. And echo chambers have some scary failure modes: mobs, cults, extremism, and worst of all political meme pages. But I’m sure you hear plenty about the downsides of echo chambers. We mustn’t forget that every advanced class in school was only possible because of the mountain of shared context we had built prior. Unsurprisingly, complex ideas require complex foundations.

I’m not sure why I had the idea to present both of these claims together in this essay because they exist in tension with one another. The more you lop thinking tools off of comprehensive frameworks the more you guarantee no one will share your strange custom artisanal context. But if you’re someone like me, just mansplaining the ideas you learned can also be pretty fun.